Court of Appeal dismisses Tesco’s appeal in trade mark dispute with Lidl

By Angela Jack

Angela Jack assesses the Court of Appeal’s recent ruling in the trade mark dispute between two UK supermarkets

The Court of Appeal has recently handed down its decision in an appeal by Tesco against findings of trade mark infringement, passing off and copyright infringement in their use of signs to advertise Clubcard prices, CCP Signs, and a cross appeal by Lidl against a finding of invalidity of the Wordless Mark.

|  |

| Wordless Mark | Example CCP Sign |

The only one of those findings overturned by the Court of Appeal was the finding of copyright infringement. The leading judgment is given by Arnold LJ. However, both Birss and Lewison LJJ also gave short judgments agreeing with Arnold LJ’s ultimate conclusions, but setting out differences in their reasoning.

Passing off

There was no dispute before the court as to the applicable legal principles for a claim for passing off. The core ingredients were identified by Arnold LJ as “(i) goodwill owned by the claimant, (ii) a misrepresentation by the defendant and (iii) consequent damage to the claimant.”

Misrepresentation

Tesco appealed that: “the judge was wrong to find that the average consumer seeing the CCP Signs would be led to believe that the price(s) being advertised bad been ‘price-matched’ by Tesco with the equivalent Lidl price, so that it was the same or a lower price.”

This formed the basis both of an appeal against the finding by Joanna Smith J of misrepresentation and Tesco’s primary ground of appeal in relation to trade mark infringement.

Misrepresentation in passing off cases is a question of fact and, therefore, the judge’s conclusion could only be overturned if ‘rationally insupportable’.

The trial judge had considered three strands of evidence before reaching her conclusion. Tesco argued on appeal that the judge was wrong to have considered that evidence at all or alternatively should have formed her own view “based on her own common sense and sense and experience and only then considered whether the evidence relied upon by Lidl confirmed or contradicted that view.”

The first strand of evidence was oral evidence from two witnesses who had sent social media messages in response to seeing the CCP Signs. Tesco argued that the judge had given too much weight to the evidence provided by one of those witnesses. Arnold LJ agreed with this although found that this error did not undermine the judge’s reasoning.

Tesco also complained that Lidl had not called any of the other witnesses who had sent similar messages in relation to the CCP Signs. Arnold LJ rejected this argument, noting: “Tesco had not provided contact details for many of the individuals in question until it was too late for Lidl to obtain evidence from them. Lidl called the only two people for whom they had contact details and who were willing to give evidence. Given that [the witnesses] had been called, the judge was entitled to treat their evidence as supplementing the evidence of the other senders.”

The second thread of evidence relied on was a number of social media messages. One of Tesco’s criticisms of the judge’s reliance on this evidence was that she gave insufficient weight to the risk that the authors of the messages may have confused Lidl with Aldi, particularly given that: (a) Tesco was carrying out a price-matching campaign with Aldi and (b) there was evidence of misattribution between the Aldi and Lidl brands more generally (indeed, in my own household both are known as L’Aldi). Arnold LJ dismissed this criticism and held that the judge had been entitled to find that the evidence did not establish that the perceptions of price matching were entirely explicable as being due to confusion between Lidl and Aldi.

The final strand of evidence was the results of a survey commissioned by Tesco prior to launching the CCP Signs. One of Tesco’s objections to the judge giving this any weight was that it had not been shown to be statistically significant. In rejecting this criticism, Arnold LJ noted that the judge had not treated it as determinative but had treated the survey “as one piece of evidence among a number of others which assisted her to gauge the perceptions of ordinary consumers, including their subconscious reactions.”

Arnold LJ rejected the suggestion that the judge had been required to form her own provisional view before considering the evidence and confirmed that she had been entitled to reach her own conclusion after doing so. In concluding that the judge’s findings of fact were not liable to be overturned on appeal and that the appeal against the finding of passing off should therefore be dismissed, Arnold LJ stated: “At first sight, the judge’s finding that a substantial number of consumers would be misled by the CCP Signs into thinking that Tesco’s Clubcard Prices were the same as or lower than Lidl’s prices for equivalent goods is a somewhat surprising one […]. In the present case the Judge’s finding was based upon the three strands of evidence I have discussed above. The judge was not only entitled to place some weight on each of those strands, but also to regard each of the three strands as reinforcing the other two […]. Standing back, I am not persuaded that her finding was rationally insupportable.”

Birss and Lewison LLJ agreed with these conclusions but Lewison LJ was more surprised than Arnold LJ by the decisions of fact reached by the trial judge. He stated, in the final paragraph of the judgment: “I find myself in the position of Lord Bridge of Harwich in the Jif Lemon case at 495: ‘If I could find a way of avoiding this result, I would. But the difficulty is that the trial judge’s findings of fact, however surprising they may seem, are not open to challenge. Given those findings, I am constrained […] to accept that the judge’s conclusion cannot be faulted in law. With undisguised reluctance I agree […] that the appeal should be dismissed.’”

Trade mark infringement

Lidl’s claim for trade mark infringement had alleged infringement both of the Wordless Mark and the Mark with Text (shown below) under Section 10(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (TMA), rather than the more familiar Section 10(2).

Infringement under Section 10(3) turns on the use of a sign which is identical with or similar to a registered mark without due cause and such that it takes unfair advantage of, or is detrimental to, the distinctive character or the repute of the trade mark.

Tesco argued that the judge was: (1) wrong to find that Tesco had taken unfair advantage of the reputation of the Lidl Mark with Text, (2) wrong in her finding of detriment, in particular that she was wrong to find that there had been a change in the economic behaviour of consumers, and (3) wrong to find that Tesco did not have due cause.

Unfair advantage

The judge found that the first of those grounds of appeal stood or fell with the price-matching allegation addressed above and accordingly dismissed it.

Detriment

This was considered on the basis that, contrary to the appeal court’s finding, the price-matching allegation had not been made out and is one of the areas where there was a divergence of opinion. Arnold LJ found that the judge’s finding that there had been a change in economic behaviour was rationally supportable. Birss LJ took a different view on this ground of appeal, stating: “However, that case on detriment, absent price matching, becomes very hard to distinguish from one based on pure dilution. Trade mark law has never gone that far and I would not wish to encourage it. I agree that Lidl pleaded a wider case but I am not convinced it was or even could be made out, absent price matching. In the result it is not necessary to go any further into this question because it makes no difference to the outcome.”

Due cause

Tesco argued that the judge had been wrong to hold that the test for due cause was a ‘relatively stringent’ one and that “[t]he mere fact that the sign complained of was innocently adopted is not sufficient to invoke the exception.”

Arnold LJ disagreed stating that there had been no error of law or principle in the judge’s reasoning and that her conclusion was one that she had been fully entitled to reach. Lewison LJ went further and suggested that there was no separate requirement of use without due cause in cases of ‘unfair advantage’ under Section 10(3): “I do not believe that this is the law. Going back to the text of section 10(3), infringement is established where ‘the use of the sign, being without due cause, takes unfair advantage of’ the mark. I would interpret that as meaning that if the sign is used with due cause, any resulting advantage is not unfair. I find it difficult to conceive of a case of unfair advantage where the sign has been used with due cause.”

In his own judgment, Birss LJ indicated his sympathy with Lewison LJ’s position but stated: “I do not think the resolution of this issue […] arises on this appeal and I prefer to leave it for an occasion in which it is decisive.”

Invalidity of the Wordless Mark

Lidl had appealed against the judge’s finding that various registrations of the Wordless Mark were invalid for registration in bad faith. Dismissing Lidl’s appeal, Arnold LJ (with whom Birss and Lewison LLJ agreed) noted that Lidl had raised 12 grounds of appeal and stated that the “multiplicity of grounds suggests that Lidl are unable to identify any serious flaw in the judge’s reasoning.”

Copyright infringement

At first instance Tesco had been found to infringe Lidl’s copyright in the Mark with Text. The unchallenged evidence at the trial had been that the Mark with Text had been developed in three states: first the stylised Lidl text (‘the Stage 1 Work’), then that text superimposed on a yellow circle with a red border (‘the Stage 2 Work’) and, finally, the blue square with the Stage 2 Work superimposed on it (‘the Stage 3 Work’). The judge found that Tesco had infringed copyright in the Stage 3 work. Tesco appealed against this decision on the basis that the judge had been wrong to find that: (1) copyright subsisted in the Stage 3 Work, and (2) Tesco had infringed any such copyright.

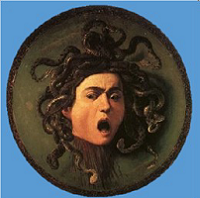

In relation to subsistence, Tesco argued that “the contribution of the author(s) of the Stage 3 Word was analogous to adding a blue background to Caravaggio’s Medusa.”

|  |

| The Mark with Text | Caravaggio’s Medusa with blue background |

However, in Arnold LJ’s view this argument was counterproductive: “Any painter will confirm that placing one colour against another changes the viewer’s perception of both. So too does placing one shape within another […]. The degree of creativity involved in the creation of the Stage 3 Work may have been low, but it was not a purely mechanical exercise, nor was the result dictated by technical considerations, rules or other constraints which left no room for creative freedom.”

In relation to infringement, Tesco raised an argument that had not been raised at trial: they argued that Tesco had not copied that which was original in the Stage 3 Work but the idea of a yellow circle in a blue square. This argument found favour with the Court of Appeal and Arnold LJ stated: “Although the Stage 3 Work is sufficiently original to attract copyright, the scope of protection conferred by that copyright is narrow. Tesco have not copied at least two of the elements that make the Stage 3 Work original, namely the shade of blue and the distance between the circle and the square. Furthermore, Lidl accepted that they cannot complain about the copying of the yellow circle in itself, because the yellow circle is original to the Stage 2 Work […]. Thus, I conclude that Tesco have not infringed the copyright in the Stage 3 Work.”

However, that victory may come as little comfort to Tesco given the Court of Appeal’s conclusions on passing off and trade mark infringement. It has been reported in the press that Tesco now plan a rebrand of the Clubcard scheme, which could cost as much as £8 million.

Angela Jack is a Managing Associate at EIP

eip.com/global/